I believe in the sun even when it is not shining;

I believe in love even when feeling it not;

I believe in God even when he is silent.

— An inscription on the wall of a cellar in Cologne where a number of Jews hid themselves for the entire duration of the war.

Four years ago, I wrote a series of four blog posts about the complicated history of the “I believe in the sun” quotation given above, and its provenance.

In the first post I wrote about the many variations of the quotation that are floating around, and how the “wall of a cellar in Cologne” attribution has been warped and distorted over the years. In the second post, I wrote that the earliest printed version I could find — in English — was from the July 13, 1945 edition of the Quaker publication The Friend, from London, but the order of the sentences was different than it is above. In the third post, I wrote about the earliest source I found for the quotation exactly as it is shown above. And in the fourth post, I wrote about why I think it’s important to get the story straight, and why it’s irresponsible and disrespectful to pass on versions of this quotation and its attribution carelessly.

In the four years that have passed since I wrote those posts, I have continued to try to track down the origin of the quotation and its story.

And now, dear reader, I have finally found a primary source.

On June 26, 1945, the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Nachrichten published a “special correspondence” from an unnamed reporter writing from Cologne. You can find the original article here, in an amazingly useful archive managed by the Swiss National Library.

The article is about Catholic resistance to the Nazis in Cologne. It speaks of the underground bomb shelters used by the Catholic community, and of disused underground passages in old buildings that the Catholic resistance used as refuges from the Gestapo. Here is the relevant section, in German:

Katholische Pfadfinder hatten seit langem nicht mehr benutzte unterirdische Gänge von alten Gebäuden entdeckt, die nunmehr wieder als Zuflucht gegen die Gestapo dienen konnten. Neun jüdische Flüchtlinge hielten sich während einer Zeit von vier Monaten dort verborgen, ohne je erwischt zu werden.

Bei meiner Besichtigung des Schutzraumes hatte ich Gelegenheit, in dieser mit allem Zubehör ausgestatteten Notwohnung mit Küche, Schlafzimmer, Wohnraum, Radio, einer kleinen Bibliothek und Oellampen den Beweis staunenswerter Erfahrung zu sehen. Die Mahlzeiten konnten nur nachts zubereitet werden, um nicht die Aufmerksamkeit der Gestapo darauf zu lenken, die tagsüber den Rauch von unten bemerkt hätte. Die Versorgung mit Lebensmitteln mußte durch Freunde erfolgen, die freiwillig Teile ihrer Rationen abgaben, um den Unglücklichen, die dort wochenlang in völliger Dunkelheit lebten, zu helfen. An den Mauern eines dieser unterirdischen Räume, die in mancher Hinsicht römischen Katakomben ähnlich sehen, steht folgende Inschrift: „Ich glaube an die Sonne, sei es auch dunkel, ich glaube an Gott, mag er auch schweigen, ich glaube an Nächstenliebe, obwohl sie sich nirgends zeigen darf“.

And here is a translation of this passage, provided by Nicholas Kontje:

Catholic Scouts had discovered underground passageways which had been unused for many years under old buildings, and these could now serve as refuges from the Gestapo. At one point, nine Jewish fugitives hid here for four months without ever being caught.

When I visited the shelter, I had the opportunity to see the emergency housing, fully equipped with a kitchen, bedroom, living room, radio, a small library, and oil lamps — evidence of a stunning experience. Meals could only be prepared at night so as not to attract the Gestapo’s attention, who would have noticed the smoke during the day. Food had to be supplied by friends who willingly gave up a portion of their rations to help those unfortunate people living for weeks in utter darkness. The following inscription is written on the wall of one of these underground rooms, which in some ways resemble the Roman catacombs: “I believe in the sun, though it be dark; I believe in God, though He be silent; I believe in neighborly love, though it be unable to reveal itself.”

Note that the reporter says that they have seen the underground shelter with their own eyes. And note that the date of publication of this special correspondence is before the publication of the article in The Friend, and likely before the date of the radio broadcast that the article in The Friend reported on.

I will write more on this discovery later, after I have had a chance to think about it further. But I do want to at least make the following points.

- “Though it be dark” has a different meaning than “even when it is not shining.” If you are underground at noon, the sun is shining, but you are in the dark.

- The sentence about God is the second line, and not the third. I had been pretty confident that this would be the case.

- The most unexpected revelation for me is the appearance of Nächstenliebe in the third sentence. Nächstenliebe can be translated into English as charity, altruism, benevolence, brotherly love, neighborly love, compassion, and so on, but I do not believe that love without a further qualification is a particularly good translation. In English, love and charity are concepts that are linked to one another, but they are definitely distinct from one another, unless you modify love with an adjective. This distinction is not a new issue… Consider, for example, I Corinthians 13:13, which in Greek uses ἀγάπη, but which has been translated to English both as “And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity” (KJV) and as “And now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; and the greatest of these is love” (NRSV). I think most readers would consider those two translations to have different meanings.

- The publication of this article in a newspaper gives an avenue for Prisoner F.B. (see here) to have heard of the story. And in his radio interview, perhaps he misremembered Nächstenliebe as Liebe? Or perhaps the radio transcriptionist misheard? Or perhaps Bertha Bracey, the Quaker who translated the German transcription into English, assumed that people would interpret love as brotherly love?

- The article speaks of nine Jewish refugees hiding for four months. The quotation at the top of this page speaks of “the entire duration of the war.” The game of telephone has already begun.

- Amusingly, if you go to the Swiss newspaper archive and search for “Ich glaube an die Sonne”, you will not find anything. That’s because the newspaper typesetters emphasized the inscription by s p a c i n g the letters a p a r t, thus defeating the OCR software’s ability to identify the words.

- And finally: These specific words change the meaning of the quotation for me. The Jews hiding underground could not see the sun; it was not there for them. And it sounds like God was silent for them at that time, too. But charity, or benevolence, or neighborly love, or compassion… well, those things were present with them at that very moment, because people were risking their lives to keep them safe, and people were sharing rations with them. Nächstenliebe was right there with them — although it (like them) had to be hidden.

I have been thinking of how the inscription might be translated, not literally, but into colloquial English that captures the spirit and meaning of the original. My favorite loose translation so far is this:

I believe in the sun, even in the darkness.

I believe in God, even if God is silent.

I believe in compassion, even when it must remain hidden.

This entire series of posts is dedicated to the librarians and archivists of the world. Thank a librarian the next time you see one — and remember, always cite your sources.

The posts in this series:

1. Look away

2. The Friend

3. The secrets of tigers

4. Conclusion

5. The source.

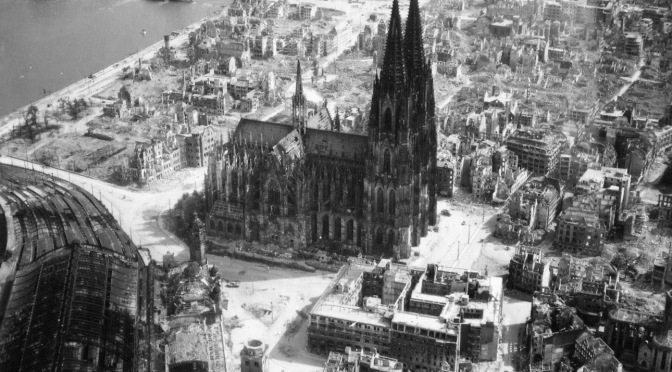

Cover image: The earliest printed example of the “I believe in the sun” quotation that I have been able to find. Cropped from a digital image of the article discussed in this post.